Aria of the Abyss: When Singing Meets the Stakes

Opera, the most heightened of art forms, finds a natural partner in the high-stakes drama of gambling. The opera house magnifies emotion through powerful voices and sweeping orchestration, making the turn of a card or the spin of a wheel feel like a matter of life and death. Composers and librettists have long been drawn to gambling scenarios because they provide instant, visceral drama—a crucible where character is tested, secrets are revealed, and destinies are sealed in a single, tense moment. From the elegant salons of the bel canto to the gritty realism of verismo, the gambling scene serves as a powerful theatrical device and a rich metaphor for the risks we take in love, power, and pursuit of our desires.

The Verdian Gamble: Power Plays and Political Wagers

Giuseppe Verdi, master of political and personal intrigue, used gambling to underscore themes of power and deception. In “Rigoletto,” the curse that sets the tragedy in motion is uttered by Count Monterone in Act I, a scene set in the Duke of Mantua’s palace during a festive party that includes gambling. The Duke himself is a serial gambler in matters of the heart, betting with women’s affections. While not a central card game, the atmosphere of risky, amoral play permeates the opera, establishing a world where human dignity is wagered and lost. More directly, in “Un ballo in maschera” (A Masked Ball), the fortune-teller Ulrica’s cave is a den of superstition and hidden risk, where the protagonist, Riccardo, gambles with his own safety by visiting incognito, setting his fateful trajectory.

Verdi’s genius lies in using the social context of gambling to expose the corrupt foundations of a court. The music in these scenes often employs dance forms like the minuet or gallop, their elegant surfaces masking the dangerous intrigues underneath. The orchestration becomes lighter, more rhythmic, and deceptively cheerful, creating a stark contrast with the dark emotions of the characters. For Verdi, the gamble was often a public performance, a social ritual where private ambitions and hatreds were played out under the guise of leisure, making the opera itself a wager on the audience’s perception of honor and justice.

The Russian Roulette of the Soul: Tchaikovsky’s Obsession

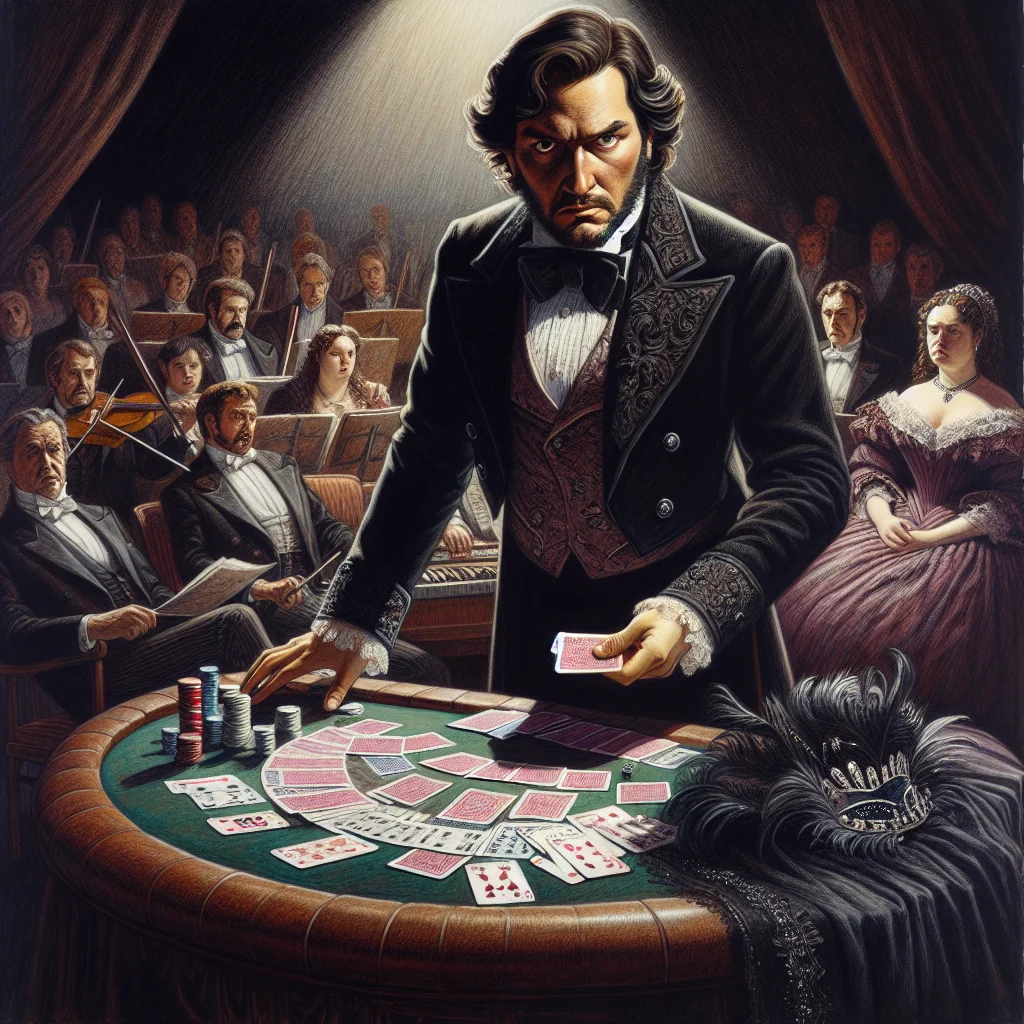

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “The Queen of Spades” (Pique Dame) stands as the quintessential gambling opera, where chance is intertwined with the supernatural and psychological decay. Based on a Pushkin story, the opera follows the officer Gherman, who becomes obsessed with learning a secret trio of winning cards from the aged Countess. For Gherman, gambling is not a pastime but an existential quest for wealth that will win him the love of Lisa, the Countess’s granddaughter. The famous scene where he confronts the Countess, leading to her fatal fright, is a high-stakes gamble with morality itself. The music is relentlessly driven, with obsessive rhythmic motifs mirroring Gherman’s crumbling mind.

The final scene, set in a gambling hell, is a masterpiece of musical tension. As Gherman finally plays the cards, believing he holds the secret, Tchaikovsky’s score builds almost unbearably. The other players sing in a detached, chant-like manner, while Gherman’s lines are feverish and fragmented. When he reveals his final card—not the expected ace but the Queen of Spades—the orchestra delivers a shattering, dissonant chord. The ghost of the Countess appears to him, and he takes his own life. Here, the gamble is a direct conduit to madness and the supernatural. Tchaikovsky uses the game as a framework to explore obsession, the illusion of control over fate, and the ultimate price of trading one’s soul for a sure bet.

Verismo’s Gritty Bet: Everyday Lives on the Edge

The verismo movement, which focused on the raw passions of everyday people, brought gambling down from aristocratic salons to taverns and street corners. In Ruggero Leoncavallo’s “Pagliacci,” the traveling players perform a commedia dell’arte play within the opera, which features a scene where the character Taddeo is caught cheating at cards. This theatrical gamble directly mirrors the real-life love triangle and betrayals among the actors, blurring the lines between performance and reality. The music here is deliberately crude and rhythmic, evoking the sound of a rustic village fair, making the stakes feel immediate and human.

Giacomo Puccini, while not a pure verismo composer, masterfully used gambling to reveal character and advance plot. In “La Bohème,” the second act Café Momus scene includes a brief but telling moment where the friends, celebrating their sudden windfall, gamble away their coins. The music is boisterous and carefree, a waltz that captures their youthful exuberance and willful ignorance of poverty. This gamble is not about obsession, but about fleeting joy and camaraderie, making the tragedy of the later acts more poignant. In “Il Tabarro,” the barge workers play dice, their game underscoring the simmering tensions and petty jealousies that will erupt into violence. For the verismo composers, gambling was a slice of life—a common, often destructive, habit that revealed the fragile economic and emotional realities of their characters.

The Musical Mechanics of Chance: Orchestrating Tension

Beyond narrative, composers deploy specific musical techniques to mimic the mechanics and psychology of gambling. The use of repetitive, spinning figures in the strings or woodwinds can evoke the roulette wheel. Staccato, percussive chords often represent the dealing of cards or the roll of dice. Harmonic uncertainty—hovering between keys or delaying resolution—creates a sonic feeling of suspense, of “not knowing where the ball will land.” In “The Queen of Spades,” the motif associated with the three cards is a chilling, ascending phrase that becomes a haunting earworm, much like a gambler’s fixation.

Recitatives—the dialogue-like singing—in gambling scenes often become more rapid and rhythmically irregular, mimicking agitated speech. Conversely, when a character is focused on their hand or the wheel, the music might suddenly become still and quiet, with only a pulsing bass line, drawing the audience into their singular concentration. The sudden orchestral crash on a loss, or the triumphant, sweeping melody on a (temporary) win, are classic operatic gestures that translate the gambler’s emotional extremes directly into the audience’s gut. In opera, the house orchestra is the ultimate croupier, controlling the tempo, building the tension, and finally revealing the sonic outcome of the wager, ensuring that the audience feels every heartbeat of the bet.