Improvisation on a Loaded Die: The Stage as a Gaming Table

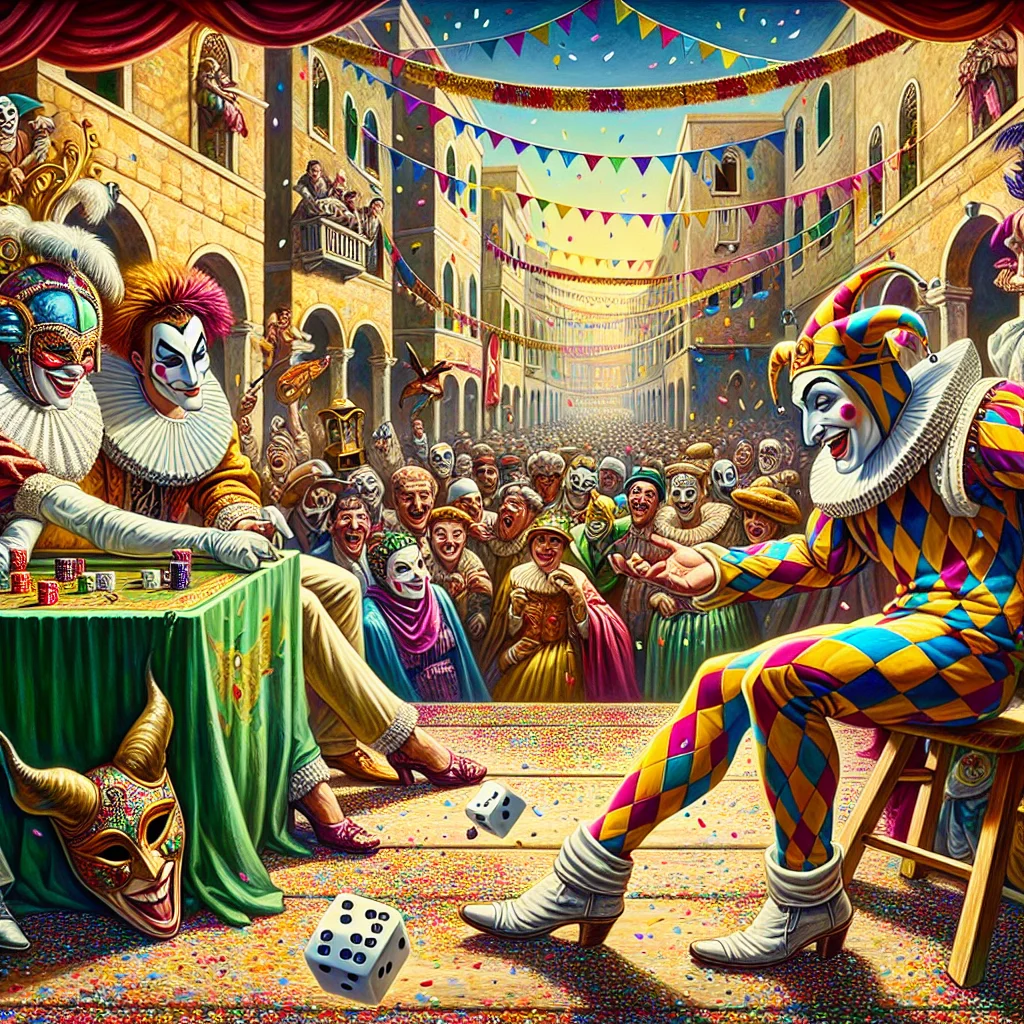

Long before the polished plays of Molière or the operas of Verdi, the raucous, street-level world of Commedia dell’Arte was weaving gambling deep into the fabric of European theatre. This 16th-century Italian form of improvisational comedy, performed by troupes of masked actors, relied on stock characters and familiar scenarios, or “lazzi,” many of which revolved around tricks, cons, and games of chance. In the temporary, topsy-turvy world of Carnival—where social rules were inverted and masks granted anonymity—gambling flourished as both a popular pastime and a potent theatrical metaphor. The Commedia stage became a laboratory for gambling archetypes: the foolish miser, the cunning servant, the gullible lover, all playing their parts in a human comedy where fortune was as fickle as a roll of the dice.

Stock Characters Holding the Cards: Arlecchino, Pantalone, and the Stakes of Folly

The iconic masks of Commedia dell’Arte are essentially gamblers in a perpetual social game. Pantalone, the aging Venetian merchant, is obsessed with money and status. His plots often involve foolish financial schemes or attempts to marry for money, making his entire life a bad investment. He is the perennial loser, the man who believes he controls the game but is constantly outwitted. Opposite him is Arlecchino (or Harlequin), the acrobatic, hungry servant. Arlecchino’s survival depends on his wits; he is a natural cardsharp and con artist, using sleight-of-hand, literal and figurative, to cheat Pantalone or others out of a meal or coin. His gambling is one of necessity and cleverness.

Other characters play their roles: Il Dottore (the doctor) gambles with his pompous, false knowledge; Il Capitano (the captain) bluffs about his military prowess, a gamble on his reputation; the young lovers, Isabella and Flavio, gamble with their hearts and futures against the obstructive plans of their elders. The interactions between these fixed types created predictable yet endlessly variable comedies centered on risk, deception, and the pursuit of desire. The audience’s pleasure came not from surprise, but from watching the familiar game play out, knowing that the clever servant would likely win his small bet against the greedy master, upholding a carnivalesque justice where the lowly triumphed through guile.

Lazzi of Chance: Physical Comedy and Theatrical Cons

The comic routines, or “lazzi,” of Commedia were physical manifestations of gambling concepts. A classic lazzo involved Arlecchino cheating at dice or cards, often with exaggerated gestures and asides to the audience. Another might see Pantalone counting and recounting his money, only to have a gust of wind (or Arlecchino’s trickery) scatter it, a visual representation of fortune’s whims. The “lazzo of the lost bet” could drive a plot: a character forced to wear a donkey’s head or perform a ridiculous task after a wager.

These physical gags translated the abstract idea of chance into immediate, visceral comedy. The roll of a dice would be followed by a huge reaction—elation so extreme the actor would backflip, or despair so deep he would collapse into a pile of limbs. This heightened physicality taught audiences to read the emotional stakes of a gamble. Furthermore, the constant breaking of the fourth wall, where a character would confess a scheme or comment on the action directly to the crowd, made the audience complicit in the con. They weren’t just watching a gamble; they were let in on the fix, enjoying the meta-theatrical joke of watching the victim on stage remain unaware. This technique directly influences modern heist films and plays where the audience roots for the clever gambler/con artist.

Carnival’s World Upside Down: The License to Risk All

Commedia dell’Arte was inextricably linked to the Carnival season, a period of licensed misrule preceding Lent. During Carnival, ordinary hierarchies and prohibitions were suspended. Gambling, often restricted by law and the Church, was openly permitted. The theatre troupes performed in public squares amid this festive chaos, where actual gambling booths, mask vendors, and food stalls created a immersive environment. The stage action reflected and amplified the real-world atmosphere of risk and revelry.

In this context, gambling on stage symbolized the spirit of Carnival itself: a temporary escape from fate, a chance to reinvent oneself behind a mask, and a celebration of luck and excess before the austerity of Lent. The fool’s victory over the miser was a Carnivalesque fantasy of social mobility and comeuppance. This connection ensured that gambling in theatre retained an aura of transgression and liberation, an association that would carry forward into later, more formal dramas. The Carnival setting framed gambling not just as a personal vice, but as a collective, cyclical ritual—a necessary venting of societal pressures through controlled, theatrical risk.

The Lasting Deal: From Improv to Modern Drama

The legacy of Commedia’s gambling tropes is vast. Molière, a keen observer of Commedia troupes, refined these types into his classic comedies like “The Miser,” where Harpagon is a direct descendant of Pantalone. The plot of “Tartuffe” hinges on a gamble of trust and hypocrisy. Carlo Goldoni, while reforming Commedia by writing down scripts, retained gambling scenarios in works like “The Servant of Two Masters,” where the protagonist’s duplicity is a continuous high-wire act. The archetype of the clever, gambling servant evolves into Figaro in Beaumarchais’ “The Barber of Seville” and “The Marriage of Figaro,” a character who uses his wits to bet on and manipulate the social order.

Even in modern theatre and film, the DNA of Commedia is visible. The fast-talking, conniving yet lovable rogue—from Bugs Bunny to Han Solo—is a direct heir to Arlecchino, always betting on his own cleverness against a larger, richer foe. The structure of the heist or con movie, with its team of “specialists” (modern stock characters) executing a risky plan, is a polished version of a Commedia scenario. By establishing gambling as a primary engine of plot and character conflict within a popular, improvisational framework, Commedia dell’Arte and the culture of Carnival dealt a winning hand to Western drama, one that playwrights and filmmakers are still playing from today.